The Oldest Views of the Mountain Town of Zschopau

by Hermann von Strauch

I.

The oldest view of the town of Zschopau may be found in the famous Book of Cities by Braun and Hogenberg, which appeared between 1572 and 1618 under the title Civitates orbis terrarum or Cities of the World.

At that time, Georg Braun (or Joris Bruin) was Canon and Deacon of the Liebfrauenkirche in Cologne. He wrote the Latin texts to accompany the illustrations, which were provided by Frans Hogenberg (or Hougenberg), the copperplate engraver born in Mecheln in Brabant, who lived in Cologne from 1590 onwards.

His view of Zschopau dates from 1617 and unquestionably takes great liberties with reality. Besides, it is also quite possible that Hogenberg never saw Zschopau with his own eyes and based his print on an older depiction. For example, it is striking that the Augustusburg as depicted in the background does not yet show its well-known silhouette, which dates from between 1567 and 1573. In the Wildeck Castle as well, we cannot recognize the architectural form created in 1545.

Braun’s text also deserves our attention. Certainly, the author was unable to bring much personal experience with our town to bear, as he admits himself, but he compensates by a portrayal of the Ore Mountains (Erzgebirge) and the time of the great silver mining rush (the Berggeschrei) in the 15th and 16th centuries that is at once interesting and realistic. Of course, he does not yet employ the expression “Ore Mountains;” for him, they are the “Bohemian Mountains.” Neither does he use the designation of “Saxony” or “Upper Saxony” for our region, but instead always uses the older appellation, the Mark of Meissen.

In English translation, Braun’s text reads as follows: S C O P A.

ALTHOUGH the Meissen province is distinguished by its fertility as well as its health climate, and thus is bedecked with many very prosperous towns and almost innumerable villages, it is certainly true that not only the fruits of the fields above the earth but also the mineral deposits below contribute to the bountiful increase in the wealth of this land. Originally, nothing could have been more barren than this entire area, where Meissen is separated from the Kingdom of Bohemia in part by harsh mountains and in part by densely forested steep rocky outcrops. Nevertheless, human greed found a way to begin rummaging through the depths of these unfertile, remote landscapes to locate unbelievable riches within them, as an enormous wave of people ran to join the race as if for plunder, and entire new towns were founded in some spots, and hamlet turned to villages and villages into towns. Among these, still quite new, but no less outstanding, is the one that is known as Annaeberga, and which immediately began building a surrounding wall in the year 1503. In brief, I can affirm that as a result of the bountiful yields from its rich ores it has blossomed to such a degree that it can claim a rightful place among more renowned towns. Not far from there, the Scopa Stream arises in the Bohemian Mountains, and after about two leagues, it crosses through the town of the same name, which the people call Schuepen in German. Its castle, which overlooks the stream, lies separated from the town on a rocky promontory, and has a splendid tower that was erected there by the town. The fields are equally well suited for fruit orchards and pasturing, and provide the inhabitants with nourishment; and they obtain a rich income from trade with the nearby ore mines. I am unable to report anything further, since I have learned nothing further that is definite from those who have more extensive experience with this town. So, I will simply add something here written by a reliable author that greatly astonished me when I read it. This report states that on the basis of public accounts, one single silver ore claim site, known as Schneeburg (Nivalis Mons), from the year 1471 on the day dedicated to Saint Dorothea, until the year 1550, was the source of an income of one hundred twenty three thousand three hundred fifty five (123,355) tons of gold for the miners and shareholders, according to their own report. Two thousand fife hundred fifty nine (2,559) tons of gold were handed over to the account of the Elector’s treasury, and almost the same amount to the account of the Hammer, according to their customs and laws. Those who unwaveringly claim that there are no ores in Germany should ponder these facts. In any case, I do believe that if Tacitus, the otherwise neither poor nor careless portrayer of Germany, were alive again, he would not only gladly erase this mistake, but much likelier would recognize Germany with its rich and happy situation (if we may truly call it good luck that is responsible for putting a stop to so many different misfortunes, whether inflicted by self or fellow men, I would say) one of the top places among the countries of Europe.

II.

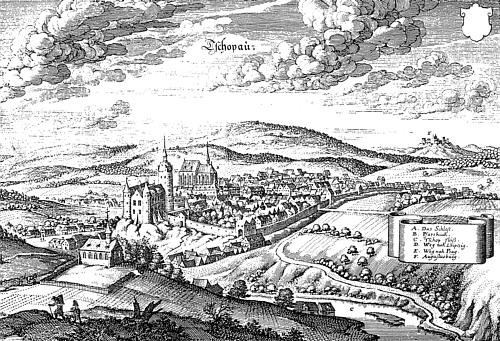

About ten years after Hogenberg etched his copperplate with the “Contrafatur” of the town of Zschopau, a pen and ink drawing of the same view appeared, drawn by Wilhelm Dilich.

Who was he? Wilhelm Dilich was born at the beginning of the 1570s, the son of a pastor in Wildungen in Hesse. He attended academic schools in Kassel and at the University of Wittenberg, and then entered the service of the Landgrave Moritz von Hessen as a “draughtsman and geographer.” He published a considerable number of smaller and larger writings, which he illustrated himself with maps, plans, townscapes and images. Because of sluggish progress in the survey of his lands ordered by the Landgrave, Dilich was unable to satisfy the demands of his patron. He fell into disfavor, but was able to avoid impending imprisonment by fleeing when Tilly was approaching with his soldiers in 1623. In the service of the Saxon nobility at that time, there was a Hessian nobleman, a military engineer, Melchior von Schwalbach. He helped Dilich flee and, in 1824, to secure a new appointment with the Elector Johann Georg I in Dresden. The Elector quickly recognized Dilich’s multiple talents, and generously rewarded his services, bestowing him with the title of Senior State Architect (Oberlandbaumeister). When he commissioned Dilich to design the wall decorations for the Great Hall in the Dresden castle, Dilich proposed, “to incorporate the views of all the noble towns in the land of Meissen above the main cornice.” His proposal was approved and Dilich was given the assignment to prepare the necessary drawings on site. With an electoral decree in his pocket, which obligated town councils and tax collectors to support Dilich with a horse and wagon, billet or meals, and whatever he might need on the trip to support his work, he traveled through the countryside from 1626 to 1629. From the numbers he assigned to his drawings, we can reconstruct Dilich’s itinerary. The twelfth stop where he made drawings was Zschopau. Unlike Hogenberg’s copperplate etching, where it is impossible to distinguish between reality and fantasy, Dilich’s drawing strikes us by its almost photographic verisimilitude. If we know Saint Martin’s Church or some details of Wildeck Castle to be any different than his drawing, these differences can all be fully documented in the archives. The way Dilich drew Zschopau in the year 1626 is the way it really was at the time.

Altogether, he completed 132 townscapes of this kind during the period. For Dilich, the most important element was the right selection of a vantage point and a frame, and for the rest he allowed nature and man’s handiwork to speak for itself, and there is nothing sugarcoated in his presentation. If his drawings nevertheless have great aesthetic appeal, it is because he was truly able to see the beauty of our homeland and knew how to capture it in his images. The documentary value of his drawings is also inestimable; shortly before the destruction wrought by the Thirty Years War, they inform us comprehensively and precisely about the appearance of our towns, with their houses, their churches, their walls, their gates, their towers and their castles.

In the 17th century, Zschopau grew to be the 18th largest town in Saxony. However, it did not belong to the “foremost towns” of the land that emblazoned the Great Hall in Dresden. Overall, Dilich completed many more drawings than he could possibly use for his original purpose; in addition, he attached Latin “descriptiones” or descriptions to his drawings. This suggests that he was thinking of publishing a book of townscapes with copperplates and texts. Perhaps the long war and his advancing age kept the artist from accomplishing this mission. At a very old age, Dilich died in 1655.

III.

The renowned creator of copperplate etchings and publisher, Matthäus Merian the Elder, is the source of a third 17th century view of Zschopau. He was born in Basel in 1593 and arrived in Frankfurt am Main after various other positions. There, he married into the de Brey publishing house, which had a near monopoly in 17th century Germany for the preparation and marketing of copperplate etchings. He retreated to Basel between 1619 and 1624 because of the turmoil of war, but after the death of his father-in-law, Merian returned to Frankfurt to secure his wife’s inheritance and to take over management of the family business. His successful pursuit of publishing could not be shaken even by the Thirty Years War. Among other pursuits, he turned to contemporary themes, which he rapidly transformed into hard cash. In 1642, he began to publish his topographies of Germany, France and Italy. On page 173 of his 1650 work, “Topographia Superioris Saxoniae, (Topography of Upper Saxony) This is a description of the best known towns and places throughout the whole Electorate of Saxony/Thuringia/Meissen/Upper and Lower Laussnitz and annexed lands” we find the following text accompanying the etching with the view of Zschopau:

Tschopau, Tschoppau, Zschopa.

A Saxon electoral castle and little town in Meissen/ and the same metallic-ore area/ on the Tshopa stream (from which this place gets its name)/ situated near Schelnberg/ Annaberg/ Chemnitz/ Ravenstein/ Wolckenstein and Thum; it is famous for the good pears/ that grow there/ and the glorious hunts and livestock raising/ to be found in this place/ and also because of its precious beer. In the year 1632 the force of the imperial forces wrought great destruction in this place, like in so many others. On the 21st of November in the year 1634, quite a few Saxon regiments were destroyed by the imperial forces/ and the little town right up to the castle/ and quite a few little houses/ where reduced to ashes/ but little by little the houses were rebuilt afterwards. The sixth part of G. Braunen’s Book of Cities commemorates this place as well under the name of Scopa or Schuepen/ and says/ that the castle is situated upon a hill above the waters/ and has a tower that is beautiful to see set against the small town.

Merian was unable to visit all the places that he pictured and described in his books, and he certainly was never in Zschopau to create the kind of true-life drawing that Dilich had produced in 1626. We are not certain if he completed our engraving himself. A number of things speak against it, not merely that Merian died in Schwalbach in the same year (1650) that the plate appeared, but also that for a long period he had assembled a competent circle of collaborators around him, who were in great measure independently active, using his well-known name, while he was running the business and organizational side of the publishing house with great skill. Even these collaborators did not travel around the countryside in order to draw the towns to be pictured on site. It was cheaper and easier to make use of earlier work done by others. For example, many territorial princes of the 17th century had hired architects and architectural engineers to render very precise pictures of their towns. However, unlike Dilich, they generally accomplished their mission in a very dry fashion without any aesthetic pretensions. Merian understood how to use such previous efforts for documentation, but was not at all inclined to simply copy them or to have them copied.

In addition, older publications were blatantly exploited—copyright protection clearly was non-existent. In our case, the townscape by Braun and the engraving by Hogenberg were used as models, and we can see very clearly how Merian and his collaborators went about creating their work. First, the transferred the shape of the most important buildings in the town, such as the castle, the church, the gates, the towers and the walls. As in the model, they were brought toward the foreground and depicted as unnaturally large. As in Hogenberg’s depiction, the town hall tower is missing. And yet, the image makes an entirely different impression: the perspective is improved, the unruly scattering of houses and roofs is reordered, the foreground is abbreviated and newly equipped, the landscape is simplified and harmonically arranged; the great sky is enlivened with clouds. In many ways, the depiction has a more credible and realistic effect, even if Merian’s presentation is no less a product of fantasy than that of Hogenberg.

But why didn’t Merian and his people use the much better, more precise and more contemporary pen and ink drawing by Dilich as a model? We actually know that Matthäus Merian’s son, who had the same name, came to Dresden in 1650, probably to petition for material to use in the planned publication. And in fact, 27 or 28 of the most beautiful Saxon townscapes by Merian go back to Dilich. So why not the picture of Zschopau? Because it was unlikely that Merian the Younger would have had the opportunity to see Dilich’s drawing in Dresden. It makes more sense to imagine that Dilich regarded him as his competitor, since he was thinking about his own publication. However, Merian must have had access to the Great Hall in the Dresden Castle, as well as permission to copy the 28 Saxon townscapes that were displayed on its walls. Since Zschopau was not among them, he was left to rely on the book by Braun and Hogenberg, unless he wanted to travel to Zschopau himself and make his own drawing there.

When all is said and done, though, Merian’s engraving is delightful and very decorative.

Hermann von Strauch